Let's put aside the yearly Easter memes about whether Jesus was a zombie or a lich or something else entirely. They are old, tired, and unoriginal.

More importantly we assume those people have completely missed these verses depicting the events prior to Christ's Resurrection.

They are worthy of the missing memes.

And about three o’clock Jesus cried with a loud voice, “Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani?” that is, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” When some of the bystanders heard it, they said, “This man is calling for Elijah.” At once one of them ran and got a sponge, filled it with sour wine, put it on a stick, and gave it to him to drink. But the others said, “Wait, let us see whether Elijah will come to save him.” Then Jesus cried again with a loud voice and breathed his last.

At that moment the curtain of the temple was torn in two, from top to bottom. The earth shook, and the rocks were split. The tombs also were opened, and many bodies of the saints who had fallen asleep were raised. After his resurrection they came out of the tombs and entered the holy city and appeared to many.

Now when the centurion and those with him, who were keeping watch over Jesus, saw the earthquake and what took place, they were terrified and said, “Truly this man was God’s Son!” ~ Matthew 27:46-54

Why are we not talking about all of these walking dead?

Wait. What?

Let's throw some of the obvious questions out there:

Who were these people? The Greek for "saints" here means "holy ones." Are these figures from the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament?

How many of these “holy ones” travel into Jerusalem?

Did they speak to anyone? What did they say?

If they woke up on Good Friday (vs 52), why didn't they leave their tombs until Easter Sunday (vs 53)?

How long were they walking around? Did they die again? Did they return to their graves unaided? Were there a bunch of poor slobs who were forced to re-intern these saint?

Why is this story only recorded in Matthew and nowhere else in the Bible?

Why is there no accounting of this event outside of this passage? Why don't historians like Josephus or Tacitus ever mention anyone else telling crazy stories about dead saints breezing through town.

We're not going to attempt to answer any of those questions. But we will posit another one.

What does your interpretation of this passage say about your respect for the Bible?

The Controversy

There have been some knock-down, dragged-out, Bible-nerd fights about this passage. People have been kicked out of churches, seminarians, and family gatherings over how these two verses are read: that was not an exaggeration. But many/most people reading this have, at best, only a vague recollection that these two verses are even a part of the Passion narrative. So of course we included it in the game.

Some history and perspectives

Though many of the early "Church Fathers" refer to this passage without any apparent issue -- including Clement of Alexandria, Eusebius, Ignatius, Irenaeus, Julius Africanus, Origin and Tertullian--, there are those who suggest that it is a late edition to the narrative that should simply be cut out. This is an interesting argument, made more so when applied.

Notice how smoothly Matthew 27:50-54 reads with verses 52 and 53 excised:

Then Jesus cried again with a loud voice and breathed his last. At that moment the curtain of the temple was torn in two, from top to bottom. The earth shook, and the rocks were split. Now when the centurion and those with him, who were keeping watch over Jesus, saw the earthquake and what took place, they were terrified and said, “Truly this man was God’s Son!”

You wouldn't have even noticed anything was missing if we hadn't told you.

However, to (badly) channel the renowned Nahum M. Sarna, we must work with the text we have before us as it stands, even when textual and historical difficulties arise. If we can't merely excise the text, we have to decide what to do with it. To that end, the primary question applied to this text has been whether to understand this passage literally or not?

The Modern Arguments

When Michael Licona questioned the literal interpretation of this story in The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach, he inadvertently set off a firestorm in regards to this passage.

Prominent figures like Norman Giesler and Albert Mohler said that this event is 100% literally, historically true, and anything less than a full-throated endorsement of this viewpoint is heretical and anathema (or close to it).

Robert Gundry argued this passage was employing the Jewish literary form of midrash-- a genre that allows for the melding of literal and metaphoric elements to present a theological perspective. Thus, the writer of the gospel was not focused on making a historical or non-historical point in this passage.

Some (wisely) attempted to sidestep this fight altogether (which is why most of your clergy have never preached from this sermon from the pulpit) perhaps seeking shelter in the wisdom of N.T. Wright's statement, “Some stories are so odd that they may just have happened. This may be one of them, but in historical terms there is no way of finding out.”

In the midst of receiving a multitude of open letters on the matter, Licona said the following in a press release:

Further research over the last year in the Greco-Roman literature has led me to reexamine the position I took in my book. Although additional research certainly remains, at present I am just as inclined to understand the narrative of the raised saints in Matthew 27 as a report of a factual (i.e., literal) event as I am to view it as an apocalyptic symbol. It may also be a report of a real event described partially in apocalyptic terms. I will be pleased to revise the relevant section in a future edition of my book” (emphasis ours).

In this last, we see an important idea which should not be lost in the midst of the "you're not a good enough Christian!" screaming matches any discussion of “the inerrant nature of Scripture” always seems to devolve into:

Historical or not, this passage must communicate

a theological point.

Some Middle Ground

This passage is a sign of the power of Jesus. That much both sides can agree to. Be it an historical event or not, like Licona we affirm that this story must be understood to be employing apocalyptic terms and symbols, as is found throughout the gospels.

In Raymond Brown's (seminary favorite) Introduction to The New Testament, he asserts that these verses may be a poetic way of describing the beginning of “the last days" or "the end times" Jesus spoke so much about. As he points out, there were signs tied to events in the life of Jesus.

At His birth a star was in the heavens. Now at His death, an earthquake shakes the earth, and the underworld lets lose its dead. In this way The Day of the Lord, The Day of Days was being ushered in through the the death of Jesus. And nothing will be the same.

The curtain in the Temple, separating the Holiest of Holies from the people, has been rent in two. Man now has direct access to God. The veil separating life and death was also punctured. Now the dead walk into the city of God.

As any English teacher worth her salt will attest, for a symbol or metaphor to mean anything, it must be rooted in reality. The abstract must have a concrete expression. Thus, this passage must point to some objective reality, though we will happily leave others to fight over the specifics of that. However, the gospels display Jesus' power over death/Death. His ministry included the resurrection of people from all walks of life (see Luke 7:11-15; 8:41, 42, 49-55; John 11:1-44).

A theme that is continued in the epistles, most notably 1 Corinthians chapter 15, which reminds that, for Jesus, the "last enemy to be destroyed is death" (vs 26) {Note: Click for an in depth look at the concept and evolution of death/Death in the Bible}.

On this point we wish to stand on Moltmann' shoulders about the nature of Jesus and resurrections of the dead:

According to the stories in the synoptic Gospels, Jesus proclaimed the dawn of God’s kingdom on earth (Mark 1.15). The kingdom comes to the sick as healing, to lepers as acceptance, to sinners as grace, and to the dead as resurrection. The raising of the dead is one of the signs and wonders of Jesus’s messianic mission (Matt 10:8; 11:5), for when the living God comes, death is forced to retreat (Is 25:8). But when Jesus raises the dead, he raises them into this life, which leads to death, and in so far this is merely an advance sign and heralding of the eternal life to come, which will drive death itself out of creation. The synoptic Gospels, which describe Jesus’s messianic mission, did not develop a ‘theology of death’. For them death is a power opposed to God whose end is at hand through the coming of the messiah. The ‘meaning’ of death is just that it will be overcome because through it the glory of the life-creating God is revealed (The Coming of God, 81).

Perhaps instead of getting bogged down in inerrancy fights, running in circles around some unanswered questions, we can focus on what's important.

Perhaps the most important part of this conversation is the realization that, whether you read this passage historically, metaphorically, or both, on Easter Sunday, more than one stone was rolled away.

Perhaps we should focus on the power of the eternal life to come and how we live right now.

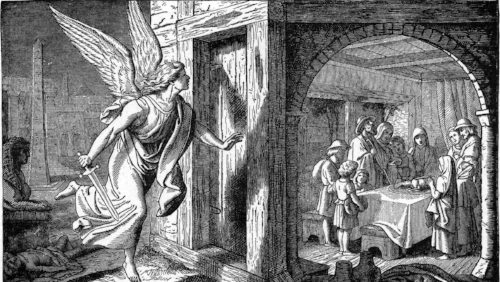

"The Vision of the Valley of Dry Bones", Gustave Dore (1866)

But what do we know: we made this game and you probably think we're going to Hell.

Note: if you want to go down a rabbit trial of white men with PhDs verbally accosting each other over who interprets Scripture better, Google "the Licona Controversy" or "the Matthew 27 Controversy" and strap in.