Note/Warning: if you arrived on this page because you read this card in our game, saw a meme or were in an argument on the internet, or in some other way came across the idea that Jesus took a whip and beat the hell out of some people, cool. But know that this Card Talk is long and in-depth. This is a seminal moment in the life and ministry of Jesus, and we don’t write for people looking to cherry-pick something out of the Bible for their argument. You’ve been warned.

We covered the events that led up and follow this moment and the aftermath in another Card Talk. However, that Card Talk was focused on the accounts given in the Gospels of Mark and Matthew (with a little Luke sprinkled in). We did not explicitly talk about this moment as recorded in The Gospel According to John.

While the story is presented in all four Gospels, as usually, John is out on a limb doing his own thing. This Card Talk will try to capture the whole scene through the lens of all four Gospels, highlighting their similarities (which are many), as well as their key differences. Together they show a picture of a Jesus who is angered and violent. And there is no intellectually honest way around that.

As our game card is based on John’s account, let’s begin with how that text tells the story:

The Passover of the Jews was near, and Jesus went up to Jerusalem. In the temple he found people selling cattle, sheep, and doves, and the money changers seated at their tables. Making a whip of cords, he drove all of them out of the temple, both the sheep and the cattle. He also poured out the coins of the money changers and overturned their tables. He told those who were selling the doves, “Take these things out of here! Stop making my Father’s house a marketplace!” His disciples remembered that it was written, “Zeal for your house will consume me.”

~ John 2:13-17 (NRSV)

Setting the Scene

Allow us to quickly highlight some background information to this story.

The Report

This is one of the few stories that all four Gospels communicate. Thus, it is either historically accurate, or all the writers felt it was just too good to pass up. As one writer opined:

So revelatory is this single moment in Jesus’s brief life that it alone can be used to clarify his mission, his theology, his politics, his relationship to the Jewish authorities, his relationship to Judaism in general, and his attitude toward the Roman occupation. Above all, this singular event explains why a simple peasant from the low hills of Galilee was seen as such a threat to the established system that he was hunted down, arrested, tortured, and executed. (Zealot, 73)

And another:

Jesus’ confrontation with the rulers in Jerusalem, perhaps mainly his condemnation of the Temple and high priests and compounded by his crucifixion, appears to have been the breakthrough event that led to the sudden expansion of the movement he had inaugurated in Galilee, ensuring that he became a significant historical figure. The expanding movement, in turn, did not merely remember his teachings and deeds, but perpetuated, cultivated, and consolidated his speech and program of societal renewal. (Jesus in Context, 197)

The Gospel According to John’s version stands apart from the Synoptic gospels (Mark, Matthew, and Luke) in a few key ways. For starters, John places this scene early in the ministry of Jesus, as one of His first public appearances, while the Synoptics all place it near the end of His ministry, and position it as one of the reasons for His execution (e.g. Mark 11:18 & Luke 19:47).

This difference is huge: instead of this being a culminating moment for Jesus, the curtain call following his Palm Sunday entrance into Jerusalem, John cast it as how Jesus breaks onto the stage of history. John wants the reader to see this moment as a microcosm of his ministry, defining who Jesus will be, what He stands for, how He rolls.

Another major difference if what brings us here: John is the only account that includes the detail of the Jesus making and using a whip.

The Location

Another consideration is the physical layout of the Temple. Most read the story with no visual understanding of the area of action. Jesus did not rush into the Holy of Holies and go hoss. He was in the Court of the Gentiles, the outer expanse which was open to all: women and men, Jews and Gentiles, unlike the rest of the Temple. As explained below, this area is where, among other things, the sacrifices were being sold for those who could actually enter into through the Beautiful Gate and present them.

Jesus’ antics would also have been within earshot (if not sight) of the Hall of Hewn Stones, the administrative offices of the Great Sanhedrin, the religious and cultural Supreme Court of Israel. Their ranks include the people who will call for Jesus’ death after this event.

The Timing

As we discuss at length elsewhere (and with a timeline), there is a difference between the Synoptics and John’s gospel in terms of Jesus’ planning time for this event. In summary:

In Matthew 21 and Luke 19, Jesus enters the city on Palm Sunday, goes straight to the Temple and starts kicking butt and taking names (before healing people and then getting into a verbal fight with the Sanhedrin).

In Mark 11, Jesus enters the city on Palm Sunday, goes straight to the Temple, finds it empty for the night, looks around, and leaves. He then returns the next day and starts kicking butt and taking names (before healing people and then getting into a verbal fight with the Sanhedrin).

As we see above, John is closer to Matthew and Luke, but adds the detail of “making a whip of cords” (vs. 15). One of the most beautiful things that has ever come out of Tumblr (which we admit is a pretty low bar) is this image [click here]: a thread which reminds the reader that Jesus made the whip and making a whip takes time. Did Jesus make the whip the night before, or walk into the Temple and slowly braided the leather in front of everyone, thinking, planning? Either way, John and Mark’s accounts present an important element to the narrative:

this wasn’t an impulsive act of righteous indignation. Jesus took His time.

Jesus knew exactly what He was doing.

What His Actions Mean

Yes: Jesus knew exactly what He was doing. He was building off a long tradition of prophetic performance. The clearing of the Temple was a prophetic sign-act: a purposeful, strategic, and calculated act of “street theater” (Crucifixion of the Warrior God, 216) for divine purposes. It’s like a physical parable with props, like how Jeremiah wore an ox’s yoke around his neck (Jeremiah 27-28), and Ezekiel ate bread baked on (or with) human shit. However, interpreting this sign-act by Jesus has caused almost as much controversy as the act itself.

Racism?! in His Temple?!

Brian K Blount argued that “God has become so angered at the religious infrastructure’s refusal to demolish the wall isolating Jews from Gentiles that God will demolish the temple that has borne little integrative fruit” (Then the Whisper Put on Flesh, 56). In other words, Jesus’ action was about the racial disparity between those who would call on His name. While this is an unfamiliar argument to many, it is borne out in the first passage of Scripture quotes in the Synoptics’ telling of the tale.

He said to them, “It is written, ‘My house shall be called a house of prayer’

~ Matthew 21:13a (Mark 11:17a, Luke 19:46a)

The “house of prayer” line “is written” in Isaiah 56, a chapter which calls upon all people, Jews and Gentiles, to “maintain justice, and do what is right” (vs 1). There is also a specific order to the Jews to not stop Gentiles from worshiping the Lord: “Do not let the foreigner joined to the Lord say, ‘The Lord will surely separate me from his people’” (vs 3a). It is within this command to extend fellowship to Gentiles that the “house of prayer” line is intoned:

And the foreigners who join themselves to the Lord, to minister to him, to love the name of the Lord, and to be his servants, all who keep the sabbath, and do not profane it, and hold fast my covenant— these I will bring to my holy mountain, and make them joyful in my house of prayer; their burnt offerings and their sacrifices will be accepted on my altar; for my house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples. Thus says the Lord God, who gathers the outcasts of Israel, I will gather others to them besides those already gathered. (vs 6-8)

The Temple is the “holy mountain” and the “house of prayer”: a place of worship, morality, and justice for all: Jews and Gentiles. Now remember the location of Jesus’ action: the Court of the Gentiles.

however one reads Jesus’s actions, His words are clear: part of His beef involved the separation between the Jews and the Gentiles, and their ability to be “joyful in [the] house of prayer,” and make the appropriate burnt offerings and sacrifices.

Fun fact: Gentiles were not allowed into the Temple to make sacrifices at all. Wonder if Jesus was upset about that? [We’ll pause for the white people who just got upset because “they’re bringing up racism again!” and need a moment.]

The more widely known perspective on Jesus’ actions (they are not mutually exclusive) is some variation of His disgust at the disenfranchisement of the poor. There were two forms of robbery taking place. The first was theft of ritual closeness between God and the gentiles discussed above. The second—the monetary theft— is what we turn to below.

JEREMIAH and the “Den of robbers”

In Matthew 21:13b (Mark 11:17b, Luke 19:46b), Jesus makes the claim that the money lenders and animal sellers have corrupted the Temple: “…you are making it a den of robbers.” This is a reference to Jeremiah 7:11 and Jeremiah’s famous “Temple Sermon.”

Some context: 600 (and some change) years before Jesus remixed his prophetic display, the prophet Jeremiah watched as the people congregated inside of the Temple (the first Temple, Solomon’s Temple). This likely happened during the high holy days of Sukkot (the Festival of Booths/Tabernacles). In other words, everyone who was anyone would have gathered for this event.

Jeremiah stood outside the Temple, in the middle of the gates (vs 2), and began yelling his sermon at the top of his lungs. Those rushing to enter can’t miss him, and those already inside are being disturbed enough to go back outside to hear him (which shows another reason Jesus is so badass in His moment: He went inside the Temple to cause His ruckus).

Here is Jeremiah’’s sermon:

Thus says the Lord of hosts, the God of Israel: Amend your ways and your doings, and let me dwell with you in this place. Do not trust in these deceptive words: “This is the temple of the Lord, the temple of the Lord, the temple of the Lord.”

For if you truly amend your ways and your doings, if you truly act justly one with another, if you do not oppress the alien, the orphan, and the widow, or shed innocent blood in this place, and if you do not go after other gods to your own hurt, then I will dwell with you in this place, in the land that I gave of old to your ancestors forever and ever.

Here you are, trusting in deceptive words to no avail. Will you steal, murder, commit adultery, swear falsely, make offerings to Baal, and go after other gods that you have not known, and then come and stand before me in this house, which is called by my name, and say, “We are safe!”—only to go on doing all these abominations?

Has this house, which is called by my name, become a den of robbers in your sight? You know, I too am watching, says the Lord. Go now to my place that was in Shiloh, where I made my name dwell at first, and see what I did to it for the wickedness of my people Israel. And now, because you have done all these things, says the Lord, and when I spoke to you persistently, you did not listen, and when I called you, you did not answer, therefore I will do to the house that is called by my name, in which you trust, and to the place that I gave to you and to your ancestors, just what I did to Shiloh. And I will cast you out of my sight, just as I cast out all your kinsfolk, all the offspring of Ephraim.dwell with you in this place, in the land that I gave of old to your ancestors forever and ever.

- Jeremiah 7:3-15

Jeremiah repeatedly condemns the people’s corruption of the Temple through their acts of injustice. And what makes it worse is that they know better, but rely on ceremony and a belief in their spiritual and moral place of privilege in the world to protect them: “this is the Temple of the Lord! We are His people! Nothing bad can happen to us!” They found out how wrong they were when the Babylonians showed up at their gates. (When will you find out?)

While we will turn to the question of Jesus’ use of physical violence in a moment, we can’t fail to see that Jesus, in channeling Jeremiah’s words, is also engaged in rhetorical violence.

Violence in/of Words

In verse 6, Jeremiah gives an all too familiar call to repentance through action. He specifically names three things that the people can do to be holy: “justice between equals…care for the helpless in the community…and faithfulness to Yahweh rather than to competing gods” (Jeremiah: a fresh reading, 29). In other words, love your neighbor and love God. Through Jeremiah, God says that if these things are done, God will “dwell with you in this place, in the land that I gave of old to your ancestors forever and ever” (vs 7). However, the people in the both temples—Jeremiah’s Temple and Jesus’ Temple—are not doing these things. And this is where the rhetorical violence begins.

In verses 11-12, God rhetorically asks if the Temple has become a “den” or “cave of robbers” in the “eyes” of the people (in other words, God says, “AM I a joke to you, Karen?!”). God goes on to say that He has eyes too, and if people don’t change their ways, they should head to Shiloh and “see” what happened there. Of course, all they will “see” there is desolation.

While Shiloh was once a site of a holy shrine, a place where the Ark of the Covenant resided, at some point in their cultural history, not only was the site abandoned, but by Jeremiah’s day, it had been razed to the ground. Other than Jeremiah’s threats, this destruction is also captured in the poetry of Psalm 78

Yet they tested the Most High God,

and rebelled against him.

They did not observe his decrees,

but turned away and were faithless like their ancestors;

they twisted like a treacherous bow.

For they provoked him to anger with their high places;

they moved him to jealousy with their idols.

When God heard, he was full of wrath,

and he utterly rejected Israel.

He abandoned his dwelling at Shiloh,

the tent where he dwelt among mortals,

and delivered his power to captivity,

his glory to the hand of the foe.~Psalm 78:56-61

When Jesus makes mention of the “den of robbers” in His temple, the assembled would largely know the stories of Jeremiah’s Temple sermon, and see Jesus’ use of his words as an indictment and a threat of utter destruction, even if He wasn’t swinging a whip, breaking things, and throwing tables.

And while the Synoptics don’t mention Jesus words about the destruction of the Temple until a few chapters later (See Mark 13, Matthew 24, Luke 21), John connects His words about its destruction directly after Jesus breaks out the whip:

The Jews then said to him, “What sign can you show us for doing this?” Jesus answered them, “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up.” The Jews then said, “This temple has been under construction for forty-six years, and will you raise it up in three days?” But he was speaking of the temple of his body. After he was raised from the dead, his disciples remembered that he had said this; and they believed the scripture and the word that Jesus had spoken. ~ John 2:18-22

Though John uses different language, and doesn’t directly quote from the same sources as the Synoptics, the inclusion of Temple destruction language indicates the writer’s awareness of that element of the narrative. But even without these quotes and allusions to The Book of Jeremiah, Jesus’ exclamation of “stop making my Father’s house a marketplace!” (John 2:16b) follows the same sentiment as “den of robbers.”

Furthermore, John displays the same focus on the corruption of the Temple through his mention of the “money changers” twice in the narrative (vs 14-15) where the Synoptics only mention them once. Which leads to the big question: why are there money changers in the Temple at all? This wasn’t an international airport, with an ever-changing exchange rate, where people are constantly afraid of getting screwed over. Actually, it pretty much was.

Money, Money, Money, Money! Monnnnneeeeeey!

According to Exodus 30:11-16, all adult males of Israel were to pay a half-shekel Temple tax annually. During the second Temple period (where we are in the story), this took place during Passover. Not all those making the pilgrimage to Jerusalem used the required currency on a daily basis. Though the Roman imperial currency was well-established throughout the empire, there were still multiple forms of currency in circulation. However, “since no Jewish shekels [form of currency] was minted during the Roman occupation, the preferred means of payment of the Temple tax was the Tyrian shekel” (“Money,” Mercer Dictionary of the Bible). As a result, the money changers, or shulḥani, were set up in the Court of the Gentiles to facilitate the exchange of money, as well as record the payment of the Temple tax.

Of course there were fees for the exchange, as well as a fee that went to the Temple itself, which varied between 4 to 8 percent. In addition to this role, they also handled currency exchanges in general (by the way, this is all attested in rabbinic sources, not just the Christian New Testament). Beyond paying the Temple Tax, there was also the issue of purchasing animals for a sacrifice. And since “the Temple alone supplied unblemished sacrificial animals” (The New Oxford Annotated Bible, note on John 2:14), worshipers needed to pay for those too.

It was this system that Jesus was overturning—a pay to pray system if you will—one that He felt was preying on the spiritual needs of the people.

To be “fair and balanced,” in our research we came across this article which, within its detailed accounting of the history of the economics of the Temple system, makes the case that Jesus was incorrect in His accusation that there was corruption in the Temple. It makes the argument that the religious leaders put specific prohibitions in place to combat such corruption. Our only response to that is to point out that we have laws on the book to stop the murder of unarmed Black people, the rape of children, and the beating of spouses, as well as prohibitions against ponzi schemes, predatory leading, and other forms of fraud. Guess what: having a law on the books doesn’t prevent the action. Ask any “sinner.”

Between all four Gospels we see the reasons and the cause for Jesus’ rage: racial separation and bigotry, predatory price-gouging, unfair exchange rates

And He wasn’t having none of it any longer.

We ran through all that really quickly, because there is another question, the one contained in the text of this card, that we find the most interesting.

Did Jesus, literally, whip anyone’s ass?

A Violent Jesus?

There is a sharp debate over whether Jesus actually hit any living creatures with the whip He made; whether He literally whipped some asses, human or donkey. And for good reason: the image of Jesus scourging someone (as He would later be scourged) is disruptive to the senses.

In the midst of his Crucifixion of the Warrior God: Interpreting the Old Testament’s Violent Portraits of God in Light of the Cross, Gregory A. Boyd argues passionately that Jesus did not hit either people or animals when he cleared the Temple for “such behavior would have flown in the face of his…public teachings about refraining from violence” that Boyd argues throughout the chapter, and is among the central messages in his two volume work on the nature of God (216).

Boyd agrees that Jesus’ actions were a calculated prophetic sign-act (214), admits that “the texts suggest that Jesus was angry,” and that Jesus made the whip (215). Be he argues that “there is simply no indication in any of the Gospels that Jesus resorted to violence when he cleansed the temple…there is no suggestion that Jesus used this whip to strike any animal or person” (215). Rather, Boyd claims, Jesus “cracked” the whip to get the assembled animals and humans to scatter. In his words, “by cracking the whip, Jesus created an animal stampede of ‘both sheep and cattle’ out of the ‘temple courts’ (John 2:15)” (215). Boyd goes on to assert that had Jesus physically assaulted someone, He would have been “arrested on the spot” (216).

Before we go any further, we want to commend Boyd for mentioning something we hadn’t considered, and didn’t see addressed by other writers/scholars. Hitting animals isn’t cool. Boyd calls to task writers who interpret the passage by saying that Jesus hit the animals, but not the humans, and that’s okay. Whether we agree with his assessment (we don’t, not fully), we are very appreciative of his explicit reminder of looking at all of God’s creation as sacred and worthy of respect. For the people in the back: animal abuse is wrong.

That said, we take issue with Boyd’s assessment in two ways.

First, Jesus screaming and cracking the whip, in essence saying, I’m swinging this thing and if you don’t get out of the way, that’s on you!”? We’ve seen this before. On The Simpsons. While hilarious, it doesn’t hold up as ethically as one might think. Because actions have consequences, sometimes unintentional ones. So, even if this interpretation is 100% accurate, it leaves us with some practical questions about “violence.”

Is Jesus responsible for any animal or person who is harmed in the “animal stampede” Boyd imagines will result from the cracking of His whip? What if a child gets trampled—one who got separated from his parents in the chaos, or was off sitting at the feet of the sages, debating the finer points of Torah—: is Jesus to blame?

Every state in the US has varying laws about “inducing panic” (like yelling “fire” when there isn’t one) and the consequences if someone gets hurt. Under the basics of rabbinic tort law—both in the Torah and the Talmud—Jesus would have been held liable for His actions if someone was hurt due to His negligence. By the law, if reasonable people can look at a person's conduct and think that the resulting damage could/should have been foreseen, that person is guilty of negligence (See these passages in Exodus 21-22, as well as Bava Kamma 52a-b, and Bava Kamma 99b). In the clip above, Bart and Lisa close their eyes while swinging and kicking, but they and we all know that the grunts and screams that followed were foreseeable. How would this not be the same for Jesus’ actions?

Yes, that is a hypothetical because the Bible doesn’t mention anyone getting hurt (would any of the Gospel’s include it if it happened?) But even if no one was actually hurt, isn’t Jesus’ actions still a form of violence? Which brings us to our second critique of Boyd’s position, his definition of “violence.”

Boyd, consciously, side-steps a concise definition of violence in his work. He includes footnotes that reflect on the need for such a definition, but does not adequately wade into those waters (though he provides resources of others who have). When talking specifically about Jesus, before addressing the whip cracking in the Temple he, again in a footnote, says:

“Since my primary concern in this section is to refute the claim that ‘violence’ in Jesus’ teachings and/or actions renders Jesus’s revelation of God compatible with the [Old Testament’s] violent portrayals of God, I am presently content to demonstrate that Jesus never caused or condoned physical harm to others” (213 n 116).

We emphasized “physical harm” in that quote, for obvious reasons. That’s the crux, right? Did Jesus physically hit animals or humans? If He did, that would be “violence.” But you have to ask yourself, is your definition of “violence” ever so limited? Really? Is it?

So swinging your belt at your child or spouse is not “violence” so long as you don’t hit them? Punching the wall, throwing dishes, screaming insults, threatening bodily harm against another person or animal is not “violence” if you don’t make physical contact? If you answered “yes” to any of those scenarios …fuck. Get help and get away from people.

Jesus stormed into the Temple, brandishing a weapon, destroying holding pens and cages, scattering chests of money, flipping over tables (that people were sitting at), all while screaming at the top of His lungs threats of God reigning down a destruction from Israelite history so utter and complete, the Bible is loathe to invoke its memory too often. How is this not violence?

To be clear: our point was never to argue that Jesus 100% opened up a can on whipping asses (can't get away from that pun) in the Temple. He might have, but as Boyd (and others) argue, there are theological problems if He did. However, as we show above, Boyd’s solution doesn’t work either.

Jesus’ act was violent

whether He hit anyone or not.

John’s account further emphasizes this point by its focus on Jesus’ “zeal.” His disciples remembered that it was written, “[the] zeal for your house will consume me" (John 2:17). While John is placing the words of Psalms 69:9 into the mouths of the disciples, understand that the Greek word employed here is not passive, it's pretty violent. It's the word Paul uses to describe how he went around capturing, excommunicating, and/or killing Christians before his conversion (Philippians 3:6). It's the word used to describe the “fury of fire that will consume” people who persist in their sins (Hebrews 10:26-27). It is a word to describe violence.

Furthermore, last but certainly not least, it must be noted that this whole Temple scene is Jesus’ fulfillment of Malachi’s prophesy of the “refiner’s fire” (anyone else just start singing parts of Handel’s Messiah in their heads? No? Just us? Cool. Cool cool).

See if any of this sounds familiar:

See, I am sending my messenger to prepare the way before me, and the Lord whom you seek will suddenly come to his temple. The messenger of the covenant in whom you delight—indeed, he is coming, says the Lord of hosts. But who can endure the day of his coming, and who can stand when he appears?

For he is like a refiner’s fire and like fullers’ soap; he will sit as a refiner and purifier of silver, and he will purify the descendants of Levi and refine them like gold and silver, until they present offerings to the Lord in righteousness. Then the offering of Judah and Jerusalem will be pleasing to the Lord as in the days of old and as in former years.

Then I will draw near to you for judgment; I will be swift to bear witness against the sorcerers, against the adulterers, against those who swear falsely, against those who oppress the hired workers in their wages, the widow and the orphan, against those who thrust aside the alien, and do not fear me, says the Lord of hosts.

~ Malachi 3:1-5 (read the rest too)

The LORD God showing up in the Temple, washing over the people like a fire that’s blazing at around 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit (the melting point of gold and silver), or the corrosive, face-melting power of an alkali solution, until they get their act together: naaaaaaaaah, that image doesn’t sound “violent” at all! #PleaseReadTheSarcasm.

The Violence Around Us: Holy?

Sometimes the impetuous for writing one of our Card Talks is someone shooting us an email asking, “hey, when you gonna write about that?!” Sometimes the spur to write is an event in the world.

Recently, and once again, the United States is wracked with the pain of dealing with its past and present sins. A new batch of unarmed Black people were murdered by police and white people who miss the days when you could lynch without repercussions. The result of these injustices have been mass protests and demonstrations, which have included some “violence.”

Let us pause here. At the time of this writing, the number of deaths and injuries from the so-called “rioters” and “looters” PALES IN COMPARISON to the number of death and injuries caused by law enforcement officers, the national guard, and military personnel in response to the protests. That’s not spin. That’s not a liberal agenda. That’s fact. Hard cold numbers.

In the midst of the bevy of commentary from arm-chair theologians and couch-surfing sociopolitical experts, the question of what “the Christian response” to the violence from protesters should be. This while business, government buildings, modes of transportation, and the infrastructures of whole municipalities were literally burning.

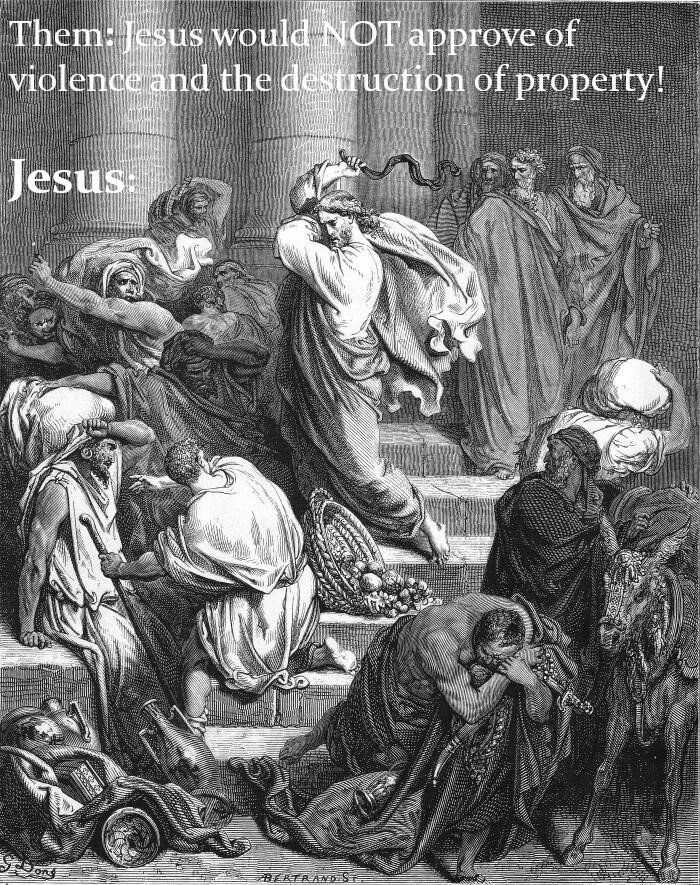

At one point, we were annoyed by something stupid someone said: a rhetorical what would Jesus do? which they answered by saying, “He would be against all this violence!” So we made this image in response, mostly as a joke, but still seriously, because it’s true.

As people watch and comment on the actions of the people in the streets, as they make statements about “protests” or “riots” or “demonstrations” or “looting,” there are those who say it shouldn’t be violent. There shouldn’t be any destruction of property. How do those people look at Jesus’ actions? Honestly asking.

On Facebook, a friend wrote a thoughtful post after seeing multiple images of Jesus tossing the Temple like the DEA serving warrants. We assume at least one of those images was ours (because y’all shared it like crazy, thanks!). She is a talented writer, so it was well crafted, nuanced, and theological sound across the board. Within its lines she included this statement:

“Please do not equate Jesus' flipping the tables of the money changers in the Temple to Jesus condoning the senseless violence and looting taking place. Of course He is angry about systemic racism and inequality. Of course we are to fight for what is right instead of turning the other cheek. Understand the nuance of what He did and said. Righteous anger is appropriate. Violence against other humans is not. Capitalism is a crippling system that traps those who cannot gain ground within it. Stealing a television benefits exactly nobody. Wrath is a sin. Anger is an energy to be used wisely.”

We agree with much of that, especially the adjectival modifiers: “senseless violence,” “righteous anger.” But obviously, we disagree with part of our friend’s statement: as we argue above, Jesus used “violence against other humans.”

Are we advocating “senseless violence”? No, don’t be a stupid pendant trying to score points in a fight you’re facing in your head. We are not advocating “senseless violence.” But we do wonder how many people, sitting in the comfort of their homes, having hypothetical conversations about the issues with no real flesh in the game, watch the news and shake their heads about the actions of “those people,” never once stopping to think about whether they ar missing displays of “righteous anger” that they are uncomfortable with. Never really stopping to think about why “those people” are out there in the first place. Or if they do, they find excuses to not think about it, and change the conversation to violence, all lives mattering, disrespecting the flag, or a host of other whataboutisms.

Many of the people in the Temple misinterpreted Jesus’ actions because it upended their world, made them uncomfortable. At best they thought He should use more peaceful methods because His message was getting lost.

At worst, they wanted Him dead.

A Simple Request

We want every white person reading this to do something. If you would be happy to be treated in the same way that society, in general, treats its Black citizens, to send us $1.

Seriously.

If you, as a white person, would be happy to receive the same treatment that Black citizens, send us $1. Here is the link. Put your money where your mouth is. Be honest.

Jane Elliott asked an auditorium full of white people to stand up if they wanted to be treated the same way Blacks are in this country. Simple task, like giving us a dollar. No one stood. (And we’re not expecting to get any money, but we’ll take it if you do). You see the point. If not, here are her words to them (and you):

Nobody is standing here.

That says very plainly that you know what's happening.

You know you don't want it for you.

I want to know why you are so willing to accept it or to allow it to happen for others?

So if you know that things are broken, that your Black and Brown brothers and sisters are being shit on, and you aren’t actively working to end it, why are you surprised by the violence? Why is it less “righteous” than if you were in the same situation?

And for those who love to throw quotes and memes and pictures of the Rev Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., extolling his “nonviolent” approach to protest (conveniently forgetting that in the aftermath of the picture they share of him marching he has dogs tearing at his flesh, fire hoses cracking his bones, and billy-clubs dislocating his shoulder-blades), these are also his words:

“Urban riots must now be recognized as durable social phenomena. They may be deplored, but they are there and should be understood. Urban riots are a special form of violence. They are not insurrections. The rioters are not seeking to seize territory or to attain control of institutions. They are mainly intended to shock the white community. They are a distorted form of social protest. The looting which is their principal feature serves many functions. It enables the most enraged and deprived Negro to take hold of consumer goods with the ease the white man does by using his purse. Often the Negro does not even want what he takes; he wants the experience of taking.”

~ As quoted in “By the end of his life, Martin Luther King realized the validity of violence,” Hanif Abdurraqib Hanif. You should read the whole thing).

But we don’t worship Dr. King. We worship Jesus.

And Jesus believed in calculated violence.

Do with that what you will.

But as always, what do we know: we made this game (and wrote this Card Talk) and you probably think we’re going to Hell.