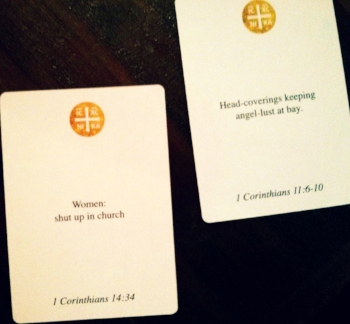

A two for one Guest Card Talk on "Women: shut up in the church" (1 Corinthians 14:34) & "Head-coverings keeping angel-lust at bay" (1 Corinthians 11:6-10) by Rev. Emmy Kegler

It’s hard to say if Paul had such low opinions of women because he was single, or if Paul was single because, even in the highly patriarchal and deeply misogynistic structure of first-century life, every nice Jewish girl in Judea took a look at the aspiring Pharisee and said, “Hard pass.”

Actually, it’s not hard to say either of those things. Paul’s statements about women-- perpetually the thorn in many contemporary women’s sides-- aren’t surprising for his time. His belief that they should be silent (1 Corinthians 14:34) and not teach or hold authority over men (1 Timothy 2:12) was standard issue. Women were treated as property, handed off from father to husband to son (if she outlived the husband). Their roles were dutiful housewives and capable mothers; the love-song of Proverbs 31 praising a competent wife might feel more romantic if the roles the unnamed woman so graciously fills weren’t the only roles women were ever offered.

Women were enshrined in biblical stories as conniving (Gen. 19:30-38, Gen. 27:5-10, Gen. 39, Num. 12:1-16, Judg. 14:15-20, Judg. 16:4-22, 1 Sam. 11-17), grievously sinful (Job 1:9, Isaiah 3:16-26, Hosea), or straight-up cruel (Gen. 16:4-6, 1 Sam. 1:3-8, 2 Sam. 6:16). Their raging sexuality took many a righteous man off the Lord’s path (Num. 25:1-3, 2 Sam. 11, 1 Kings 11:1-6, Prov. 2:16-19, Prov. 5:3-23, Prov. 7, Prov. 23:27). When God accused Israel of idolatry and infidelity, the go-to metaphor was that of a whore (Is. 1:21, Is. 23:15-16, Jer. 3:1-6, Ezekiel 16:15-52, Ez. 23, the book of the prophet Hosea, Nahum 3:4-7). If a woman was pure of heart, she might be lucky enough that her brothers would defend her honor when she was raped (Gen. 34:1-31, 2 Sam. 13:1-22), but not always (2 Sam. 11, again). If they managed to obtain a semblance of power and respect, it was often because they were clever enough to undercut the system (Gen. 38:12-23, Ex. 1:15-19, Josh. 2:1-7) or participated in the colonizing violence of the men around them (Judges 4-5).

In the time the New Testament was written, women could not initiate their own divorces or testify as a witness in court. There were of course heroines whose faith and obedience brought them great renown, successful husbands, and many children (e.g. Ruth, Hannah, Esther), but they stood out against a wide backdrop of presumed dishonesty.

In short: women got a rough deal.

Paul’s words, then, are not all that surprising.

Head coverings were not uncommon in his day, both as practical protection from desert sands and as deference to easily arousable men. Just as bra straps and yoga pants are considered too distracting for teen girls to wear to co-ed classes, the uncovering of a woman’s hair in Middle Eastern first-century practice was thought to provoke male lust.

Paul’s reiteration of the need for long-but-covered hair is a standard response to the difficulty in navigating newly integrated Jewish and Roman communities (such as the church in Corinth), where the long-held Jewish practice of head coverings and propriety came up hard against upper-class Roman women who demonstrated their status through elaborate hairstyles. Just as Paul instructed the Corinthian church to conform their worship practices to proper religious standards by rejecting idol worship (1 Cor. 10:14-22), and to eat in respect to those around them (1 Cor. 10:23-33), he now asks women who view head coverings as a sign of poverty or oppression to see them as a symbol of respect for the men who have authority over them.

But not just respect to the lusty men around them -- respect to “the angels” (1 Cor. 11:10).

For those of us raised with visions of vaguely androgynous, entirely sexless, winged messengers, this phrase can be derailing. Paul may be referring to a Jewish interpretation of Gen 6:1-3, when the "sons of God" bear children by the "daughters of men." These angels were tempted by the beauty of human women, and although they were the fathers of "warriors of renown," some Jewish scholars connected the spreading wickedness of the time before Noah with the sexual relationships between angels and women. Then again, Paul was writing to a community that was both Hebrew and Greco-Roman, which meant some of them might have had no idea of this mythical story of angel-human procreation. Thus, some other scholars argue that Paul was referring to angels who were joining with the church in worship, and would be offended by uncovered female heads because of the affront to the men present. Either way, we're not entirely sure what Paul might have meant at the time -- or what it means for us today.

Paul’s continued subjugation of women just a few chapters later isn’t much of a surprise either. Again he reiterates common practices of his day, where women were not permitted to speak in public mixed-gender groups.

Women were far less trained in scripture and public reasoning than men, so even in a philosophical setting where dialogue and questions were encouraged, women were far more likely to ask elementary questions that were considered foolish or derailing. They were, perhaps, like a ten-year-old who has so deeply enjoyed the interactive children’s sermon that she now wants to answer back during the main message as well. Paul offers a path to knowledge for these curious women: ask your husbands at home. Society has better educated the men in both religious and philosophical matters, so to refer the woman to her husband would not have been unusual. Without the benefits of today's mixed-gender adult forums where questions and dialogue can be celebrated, the best (or perhaps only) option for educating new female converts was to have their husbands pass the information along.

Paul's scathing words to women speaking in church might make sense in the face of their uneducated and disenfranchised cultural status. But interestingly enough, Paul recognizes that women do speak aloud in the Christian churches of his day.

Swing back to the head-coverings in chapter 11 and look at verse 5:

...but any woman who prays or prophesies with her head unveiled disgraces her head -- it is one and the same thing as having her head shaved.

Prayer and prophecy, in this conversation, are not silent actions. Paul is in the midst of addressing questions the Corinthian church had posed, which included the proper structure and regulation of worship. Prophecy is specifically addressed in 1 Corinthians 14, where Paul describes it as work that "builds up the church" (14:4-5). The Spirit was falling so heavily on the church in Corinth that speakers of tongues, interpreters, those with revelations, and prophets were in danger of spontaneously stumbling over each other, creating a cacophony that worshippers could not follow (14:26-28). Prophecy and prayer, in the Corinthian church, were not received and spoken in private but were gifts of the Spirit for the building up of the body of Christ and the church of God.

Thus, in Paul's first letter to the Corinthian church, we witness a variety of roles and expectations for women. They were expected to keep their hair long and their heads covered, and the uneducated and curious were to ask their questions outside of worship. But women who had received religious instruction (either from their husbands or even from Paul himself) and who had received gifts from the Spirit for prayer or prophesy were permitted to use those gifts for the "building up" of the church, without reference to only speaking in single-gender groups. Paul’s patriarchal responses to the presence of women in churches are, in the context of his day, not surprising. And so on.

In the first century, the subjugation and silencing of women was standard issue, and shouldn’t come as a surprise. What should come as a surprise is that Paul was participating in it.

Paul had already been well exposed to the idea that longstanding tradition didn't lay the sole foundation for Christian faith; he advocated, on an unpredicted and radical level, for the end of circumcision as a requirement for belonging to the people of God (Gal. 5:2-12). He was also no stranger to the support, even the co-ministry, of women.

Paul happily accepted the help of many women throughout his journeys, including the wealthy (and likely unmarried) Lydia who, along with other women by a Macedonian riverbank, learned directly from Paul, Silas, and Timothy without having to ask her husband first (Acts 16:13-15). Priscilla and Aquila worked with Paul as missionaries and educators, including correcting the errant teacher Apollos (Acts 18:24-28). They were a husband-and-wife team -- or, more correctly, a wife-and-husband team; of the six times they are mentioned in the New Testament, Priscilla is named first four times. (This, unlike Paul’s “women should not teach men” rules, was highly unusual.) In addition, Paul sent his great letter to the Romans by the hand of Phoebe, whom he recommended as a deacon to be welcomed “as is fitting for the saints” (Rom. 16:1-2) -- and if the church in Rome held to typical Greco-Roman letter-writing and -receiving, Phoebe not only carried the letter from Judea to Rome, but read it aloud when she arrived.

Paul had plenty of exposure to intelligent, faithful, and outspoken women whose service to the church went beyond casseroles and secretarial duties. But he, like many, remained in bondage to the prevailing ideals of his day. When Paul was faced with clashing cultural issues in Corinth, instead of living into the radical vision of “all are one in Christ Jesus” (Gal. 3:28), he fell back on standard-issue misogyny and patriarchy to institute order.

With the number of women active as leaders in Paul's early churches, using his words to prohibit any female teachers or preachers today becomes highly suspect. Paul relied on the ministry of women to spread the gospel. We can't ignore, either, that Paul's use of key women in evangelical roles failed to lead him to a dramatic realization that all women should thus be freed to ask curious questions during worship or to pray with their heads uncovered. Paul, like all followers of Christ, is still bound by his own time and place.

Perhaps the best way to center a consideration of the roles of all believers is to return to Paul's theme in the rest of the Corinthian letter: that all things should "be done for building up" (14:26).

Do the roles we offer members of the church today celebrate and recognize their Spirit-granted gifts? Do our expectations about behavior and dress serve only the insiders, or do they welcome the outsider (14:16) to participation and faith as well?

Just as when the Corinthian church faced these questions, there are no simple answers now. To be willing to admit when we are wrong, to let go of cultural expectations in order to more greatly welcome the good news of Christ, is a journey we will never stop taking -- at least, not on this side of the mirror.

* [At the time of original posting]

Rev. Emmy Kegler is pastor of Grace Lutheran Church Northeast in Minneapolis, Minn.

She received her B.A. in religion from Saint Olaf College and her Master’s of Divinity from Luther Seminary.

She is the founder and editor of queergrace.com, a free encyclopedia dedicated to curating the best content from around the internet on LGBTQ life and Christian faith. You can find her sermons at emmykegler.com/sermons and her cat pictures on Twitter at @emmykegler.

She would like it clearly known that she is, in fact, a woman.

!["Women: shut up in the church" (1 Corinthians 14:34) & "Head-coverings keeping angel-lust at bay" (1 Corinthians 11:6-10) [Guest Card Talk]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55a9a1e3e4b069b20edab1b0/1471403439167-JVYZP3DIZOVAMGG7YAOI/2013-10-21-UNwomenad2.jpg)