"For I know the plans I have for you," declares the Lord, "plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future." (Jer 29:11)

Oh how good Christians love this verse as long as it is taken completely out of context.

In the 29th chapter of Jeremiah, the prophet writes a letter to the people in Exile: the people who have been taken away as captives from their homes. People in pain and mourning. The people writing Psalm 137 and wanting the heads of enemy babies dashed against rocks. [More on that here]

The above words are the most famous from this letter because they are so comforting. But they are only some of Jeremiah's statements to them. Good Christians tend to ignore the rest of the words, because they can be as jarring to our modern senses as they must have been to the hearts of the original audience. Before Jeremiah relays God's plans for a hope-filled future, he outlines the present God wants the people to live in.

Paraphrased, "Thus says the Lord":

Make yourself comfortable. Buy a house. Make it look nice. Plant some flowers and crops. Eat something. (vs 5)

Get married and make a lot of babies. When they grow up, find them spouses. Then spoil your grandkids. (vs 6)

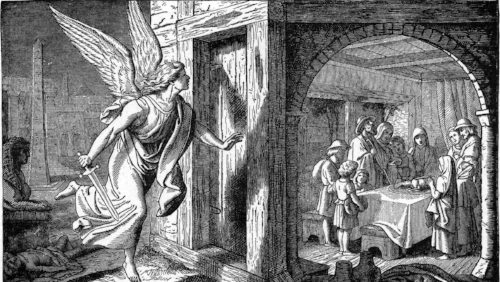

Pray that only good things will happen to your oppressors. Yes, I said, "good things." Not bad. And if anyone tells you that it's My Will for bad things to happen to them, or for all of you to leave Exile, to be rescued, they are liars. I want all of you to stay there. (vs. 7-9)

It's going to be at least 70 years until I save the people. You're probably going to die there. (vs. 10)

For surely I know the plans I have for you, says the Lord, plans for your welfare and not for harm, to give you a future with hope. (vs. 11)

A good Christian has a habit of making this his/her "life verse" without acknowledging two things:

1. The "you" in the passage is plural, not singular. God is speaking to the people as a whole, not one individual.

2. God was asking the Israelites in Exile to accept the situation as it was presented, and continue to live and serve.

The people who heard these words were told that they would die in Exile, but their children and grand-children would survive. Their descendants would live in the promised future. Thus these were not words about individual salvation, but rather communal commission.

In the midst of the captivity, under oppression, when things were not as they should be, God asked them to stay faithful and teach their children how to do so as well, even though they would not see home again.

Perhaps God asks the same thing of us as well. (But who wants that as a "life verse"?)

Perhaps this is why the Church and the Synagogue has upheld the example of Esther and Susannah, Hananiah, Mishael and Azariah, and the prophet Daniel: young people who were raised to stand strong and survive in an oppressive culture by their families. Even though the ones who raised them didn't make it out alive. Even though they didn't make it out alive.

Perhaps we could apply the words of this letter to our lives personally by twisting them to say that God will deliver us individually from some present or future aliment if we view our selves as the Exiles and their children and grandchildren in the text. But this seems like a stretch.

Perhaps it is better to read them in context and see them as words which teach us to hold on, to endure, to encourage others in our community when we are going through trouble, when certain realities will not change for us.

Perhaps we can continue to love others regardless of our fate, and find more appropriate passages which speak to God's rescue of our individual lives.

But what do we know: we made this game and you probably think we're going to Hell.

![O Come, O Come Emmanuel (Isaiah 7:14) [An Advent Card Talk]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55a9a1e3e4b069b20edab1b0/1483161046976-X5VJE3CMP9T957O72EII/3d-wallpapers-light-dark-wallpaper-35822.jpg)