"Seriously God, what the f . . . ?"

~ Too many hearts from the beginning till now.

Here is the harsh reality: over 80% of the psalms contain some measure of complaint or request for assistance from God. Well over 1/3 of the Psalter are psalms of lament, what Walter Brueggemann calls psalms of disorientation. These are the psalms that record the loss of stability, the loss of equilibrium from our lives. Conflict and trouble have crept or charged in. The world is not as it should be. We are clawing at the sides of a dark pit, while our ever-present enemies taunt our pain like a dangled rope.

In much of modern western Christianity, psalms of lament are disrespected. If not completely ignored, they are made into songs, included in sermons, and thrown into bad Christian self-help books by cutting out the cries of pain and focusing on the possible happy endings. Pain is only seen as a path to progress. Hurt paves the road to heaven.

Troubling words and images are revised or culled altogether, and calls for vengeance have little place in polite churches. There is no asking YHWH to destroy enemies like salt does a snail, or to make those who harm us like a stillborn fetus (Psalm 58). It is inappropriate to bestow heavenly blessings upon those who smash the oppressor’s babies against jagged rocks (Psalm 137). None of that fits polite church culture. That level of pain is censored.

Similarly, Psalm 88 is forgotten – so forgotten it is not even included in the Revised Common Lectionary. Why? Because Psalm 88 doesn’t play nice with the other psalms: She’s the rebel who said to hell with biblical poetic conventions, I do what I want.

There is a structure that all psalms of lament follow. They contain 1) an address to God, 2) the raising of complaints and/or petitions to God, 3) a confession of trust in God, and finally 4) a promise to praise God once He comes through. In some respects, psalms of lament are how some issue fox-hole prayers: “God, shit just got real. I need Your help. Even though the situation looks bleak, I know You got my back. Thank You in advance. I owe You one.”

All psalms of lament follow this basis structure. All of them contain a petitioned problem but end in pronounced praise. All of them. Except Psalm 88. It is the only psalm without a turn toward hope, praise, or promises to God.

More than that Psalm 88 is an indictment of God: The Lord sits not on His throne but on the witness stand.

O Lord, God of my salvation,

when, at night, I cry out in your presence,

let my prayer come before you;

incline your ear to my cry.

For my soul is full of troubles,

and my life draws near to Sheol.

I am counted among those who go down to the Pit;

I am like those who have no help,

like those forsaken among the dead,

like the slain that lie in the grave,

like those whom you remember no more,

for they are cut off from your hand.

In the sleepless night, we cry, we beg for God to hear our prayer, but hear no answer. Our soul full of troubles, our life on the brink of death, we feel forgotten by silent skies and lead-covered clouds. The only thing we are sure of is the source of our pain, the one who stands accused:

You have put me in the depths of the Pit

in the regions dark and deep.

Your wrath lies heavy upon me,

and you overwhelm me with all your waves.

You have caused my companions to shun me;

you have made me a thing of horror to them.

I am shut in so that I cannot escape;

my eye grows dim through sorrow…

From the witness stand, the divine is silent. The Almighty seems to plead the fifth. But still we press the witness for answers:

But I, O Lord, cry out to you;

in the morning my prayer comes before you.

O Lord, why do you cast me off?

Why do you hide your face from me?

Still no answer is forthcoming, only a realization:

Wretched and close to death from my youth up,

I suffer your terrors; I am desperate.

Your wrath has swept over me;

your dread assaults destroy me.

They surround me like a flood all day long;

from all sides they close in on me.

You have caused friend and neighbor to shun me;

my companions are in darkness.

And there the psalm ends. There is no turn towards the good. There is no easy resolution or a nod toward the possibility of one. It ends emotional, evoking the words of a grief-stricken C.S. Lewis: “The conclusion I dread is not 'So there's no God after all,' but 'So this is what God's really like. Deceive yourself no longer.’” ~ A Grief Observed

What do we do with this? First remember our humanity, and the humanity of the author.

“The Psalms, with a few exceptions, are not the voice of God addressing us. They are rather the voice of our own common humanity – gathered over a long period of time, but a voice that continues to have amazing authenticity and contemporaneity. It speaks about life the way it really is, for in those deeply human dimensions the same issues and possibilities persist. And so when we turn to the Psalms it means we enter into the midst of that voice of humanity and decide to take our stand with that voice. We are prepared to speak among them and with them and for them, to express our solidarity with the anguished, joyous human pilgrimage. We add a voice to the common elation, shared grief, and communal rage that bests us all.” ~ Walter Bruggemann, Praying the Psalms

Second, we remember the reality of our perception. Sometimes God is hidden from our sight, silent to our ears, beyond our grasping, bloodied fingers. And that is why this psalm is so beautiful and appropriate to complete the Psalter.

It is present to say the questions “why?” and “how long?” are appropriate. That asking “what did I/he/she/we/they do to deserve this?” is valid.

That it is okay to scream, even at God, because the lines of communication are still open: at least you’re still talking.

And besides, God can take it.

But what do we know? We made this game and you probably think we’re going to Hell.

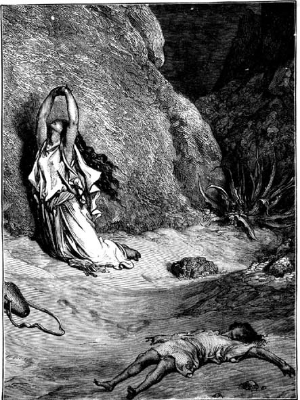

"Hagar in the Wilderness," Gustave Dore

If the above didn't drive you to drink, then you should read about why “There really aren’t enough good hymns written about_______”

![O Come, O Come Emmanuel (Isaiah 7:14) [An Advent Card Talk]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55a9a1e3e4b069b20edab1b0/1483161046976-X5VJE3CMP9T957O72EII/3d-wallpapers-light-dark-wallpaper-35822.jpg)